This week at Symphony Hall, the Tanglewood Festival Chorus is tackling an unusual piece. It’s the American premiere of a contemporary work co-commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, first performed in London in March 2023. The piece is titled The Dong with a Luminous Nose, based on the Edward Lear poem of the same name. So for you concertgoers and interested choral bystanders, here’s a peek behind the scenes as we wrap up our study of the piece and head into the final rehearsals.

Why are we singing about a Dong? (And stop laughing.)

Edward Lear is known for his nonsensical poems, limericks, and drawings — call him a more melancholy Lewis Carroll, or perhaps a Dr. Seuss for adults of the late 1800s. More of us may be familiar with his The Owl and the Pussycat… which, once read aloud, may induce similar giggles from the puerile pre-teen in all of us. His works invent nonsense characters like the Bò, the Pobble, the octopod Discobboloses, the Quangle Wangle… and the Dong. In fact, we learned The Dong with a Luminous Nose is a sequel to Lear’s poem The Jumblies, which first describes the titular travelers who then join the Dong on the great Gromboolian plain before abandoning him.

In her program notes, composer Elena Langer describes how Lear’s poem has everything music wants. You’d like a love story? Songs and dances? Fantastical landscapes? The narrative has them all, along with an emotional backdrop of longing and hope, of light and sadness. In singsong verse, the poem tells how the Dong falls in love with a green-haired, blue-handed Jumbly Girl, only to have her vanish over the sea. Her departure drives the Dong to madness. He then spends the rest of his days seeking his lost love with the help of a contraption that attaches a lamp to his nose.

Langer describes her composition as “a cross between a cello concerto, an opera for chorus, and a symphonic poem.” It’s fitting that the work is hard to categorize, because so are Lear’s poems – I’d even say they both delight in being uncategorizable. Contemporary adventures like this one are a refreshing change from the “dead white European men” we’ve already learned to appreciate.

Made-up motifs can characterize made-up words

One characteristic of the poem’s text is how it introduces unfamiliar nouns. For instance, besides the Dong and the Jumblies, you have the Oblong Oysters, the Twangum Tree (not to be confused with the Bong-tree), the Zemmery Fidd, and the Hills of the Chankly Bore.

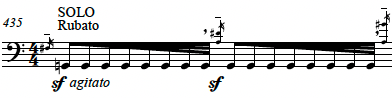

Langer explains in her program notes that she wanted to instrumentally mirror how Lear makes up words, using normal timbres in unusual combinations. So orchestrally we have sliding strings, the always nifty-sounding flexatone, and woodblocks. We have cello cadenzas with acrobatic leaps, sudden pizzicato moments, and accelerating tremolos (with a notation I’d not encountered before, pictured below). We have time signatures capriciously swapping from 3/4 to 4/4 or 5/4, except when we’re in a waltz-y 3/8. Likewise, the key signature or tonality shifts rapidly to align with the mood as the story evolves. Throughout the piece the cellist often gives voice to the Dong — his excitement, his mourning, his madness, and his ultimate obsession of finding his lost love. The chorus swings between a dark narration, pastoral cavorting during the happy days, and embodying the Dong’s lament and searching.

Throughout our study of the piece, I’ve found myself fascinated and challenged by three musical ideas:

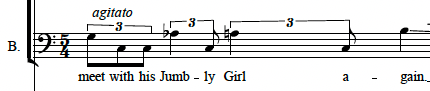

The three-note near-octave motif. Many of the bass lines have this distinctive and tricky shape, where the top note is a major 7th (i.e., one half-step short of an octave) above the bottom note. This figure occurs, sometimes in a rising sequence, often to represent the Dong’s struggles and madness.

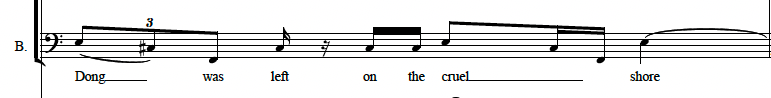

The increasing intervals motif. As the basses tell the story of the Dong searching farther and farther away for his lost love, our melodic line holds an anchor “do” note and then jumps to larger and larger intervals… a minor second and back, a major second and back, a minor third, a major third, and so forth.

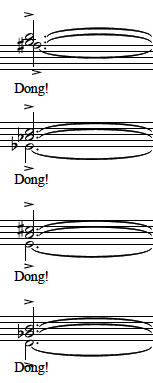

Tone clusters of superimposed major chords. To represent the Dong’s mood — often when he’s angry or confused — the chorus occasionally splits into twelve parts, with each voice anchoring around major triads that aren’t particularly related to each other harmonically. We tune to each other within each group.

The challenge, as with any contemporary music: learn to unlearn

From the very beginning of each rehearsal, James Burton has modified his warmup exercises with an eye towards these musical challenges. We’ve jumped between ever-increasing intervals. We’ve formed chords then shifted to other chords, and fought to hold notes a minor 2nd away from each other. We’ve tried to ingrain that odd major seventh interval into our heads from the three-note motif.

That three-note motif has been particularly vexing — the natural tendency is to sing an octave, not the major 7th. I’m sure many others have also been banging that interval out at home on the piano trying to retrain our brains to hear it, and drawing up arrows in our scores reminding us it’s not as far a leap as we think it should be.

Because the accompaniment is often so active, the spacing of the notes on the page is not always in line with their duration. Couple that with the shifting time signatures, and it’s easy to get lost within a measure. I wish I could say that my ability to read music was impervious to those variations, but alas, I catch myself holding quarters as halfs, treating eighths like sixteenths, moving my eyes too slowly, and getting caught without breaths (see measure 38, below!) As a result, most of my vocal score now has vertical lines marking the beats, and giant checkmarks reminding me when to drop my diaphragm and grab some oxygen, in unison with my section, before an upcoming phrase.

These challenges are further exacerbated by the rhythmic variations throughout the piece. Getting all the basses to stay in sync for what’s effectively a recitative, when it’s jumping between triplets and sixteenth-plus-dotted-eighth… academically we know how to subdivide and keep that pulse, but at our speed and intensity, all too often it’s an educated guess (such as making sure beat 2 & 4 of measure 32, or the first and last notes of measure 36, below, are not counted as triplets.) Let’s just say in the one existing recording of this piece from the London performance, our knowledgeable ears can hear that chorus struggling to agree on some of these rhythms and entrances. You just can’t be on autopilot for any of it — it demands full concentration and a lot of prep work retraining your instincts.

I personally go through the same stages with preparing any contemporary piece. First I listen to it, and recoil in horror at the nonstandard progressions, unstructured atonality, and experiments in rhythms. Then as I slowly commit to the piece, I get a better idea of the composer’s intent, and I begin to marvel at the genius of decisions made to convey story, emotion, and concepts through the context of the music. By the end of it, I’ve fully bought into the performance, I no longer notice quirks or oddities that would startle a first-time listener, and my family and friends become sick of me explaining why it’s such a cool piece.

The Dong with a Luminous Nose is no different — I’ve gone from snickering at the title to discovering its intricacies and now embracing its word painting and storytelling. I hope many readers get to experience this concert, either live at Symphony Hall or on the WCRB livestream this Saturday.