There are weeks when the digital hum of the world becomes a white noise drowning out the signal. When that happens, I’ve found getting back to creating in any form is a good reset for the soul. Perhaps there’s no better way to do that than to step onto a stage and disappear into the luscious layers of Brahms’s choral works.

This weekend’s two pieces, Schicksalslied (Song of Destiny) and Nänie (Song of Lamentation), have been a fantastic way to musically “touch grass.” You don’t need to be a choral scholar or a classical devotee to be pulled in by the harmonic gravity of Brahms’s writing, to find yourself moved by these pieces, and to get your head back on straight about what’s important.

The Dichotomy of Destiny

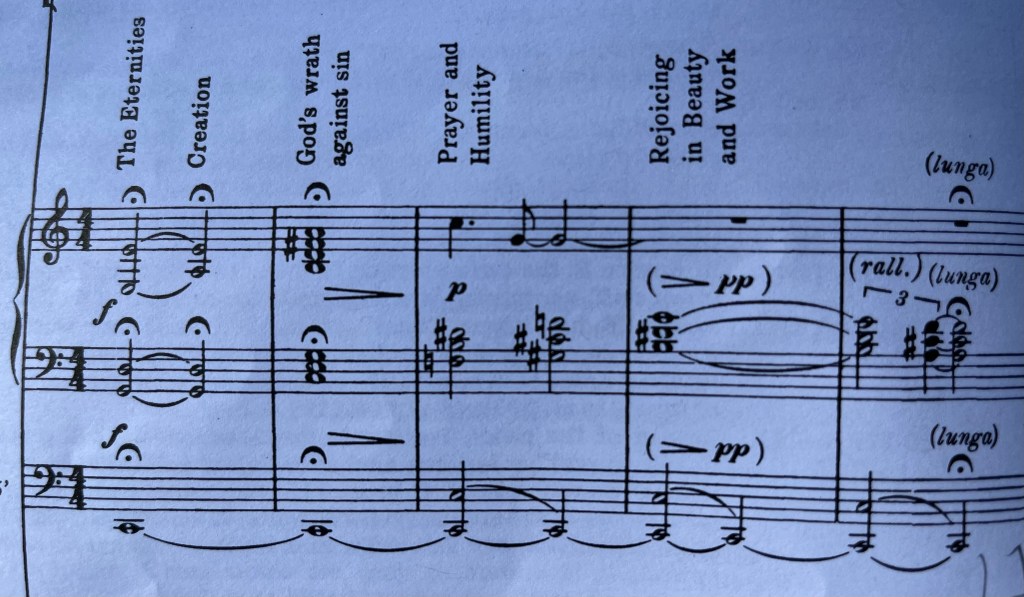

The program begins with Schicksalslied, a musical study in contrast. Inspired by the text of a Hölderlin poem, Brahms sets up a stark dichotomy: the gods moving timelessly in heaven versus the rest of us down here on Earth.

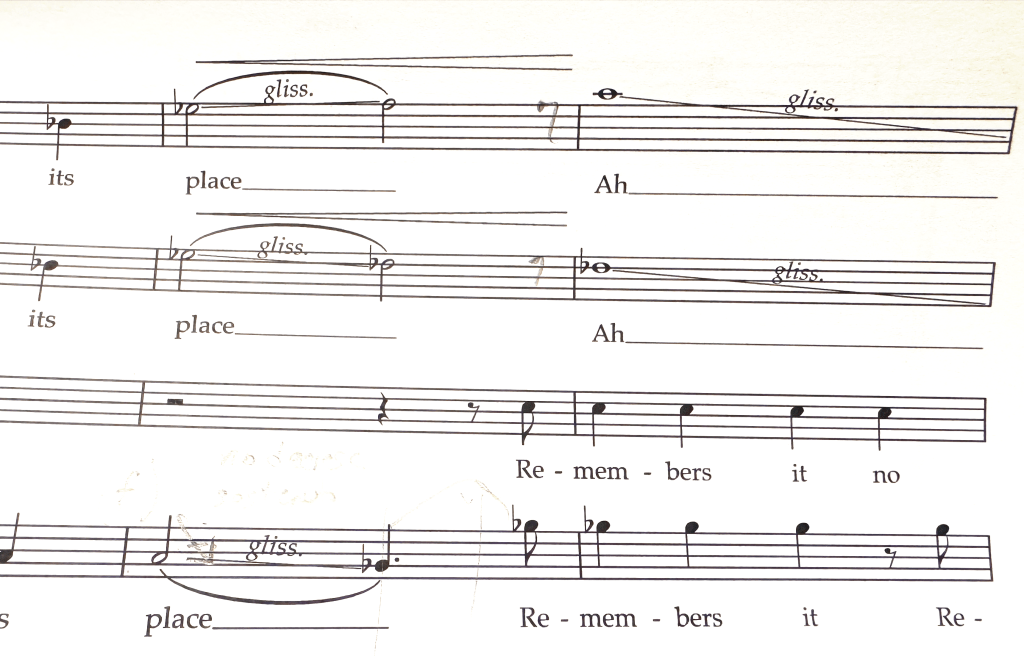

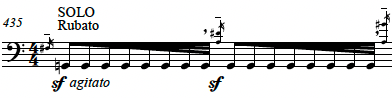

The opening movements are ethereal and smooth—it’s celestial beings treading on clouds, untouched by time, unworried about their fates. Then the floor drops out. The music shifts into a chaotic, driving force that mirrors the human experience: we are “tossed like water from cliff to cliff,” unpredictably, violently, with no place to rest, destined to disappear below.

As a singer, the challenge is to move that struggle from your vocal cords to your face. It’s not enough to sing the notes; you have to radiate that uncertainty, that frantic search for a handhold, until the very end when the music takes an unexpected turn back toward the light. I personally love to pour all my frustrations into that second half—everything from the bad weather and subway trains not working to shaking my fist at the state of the world. That catharsis is rewarded by the return of the ethereal music at the end, signifying a return of hope.

The Holiness of the Klaglied

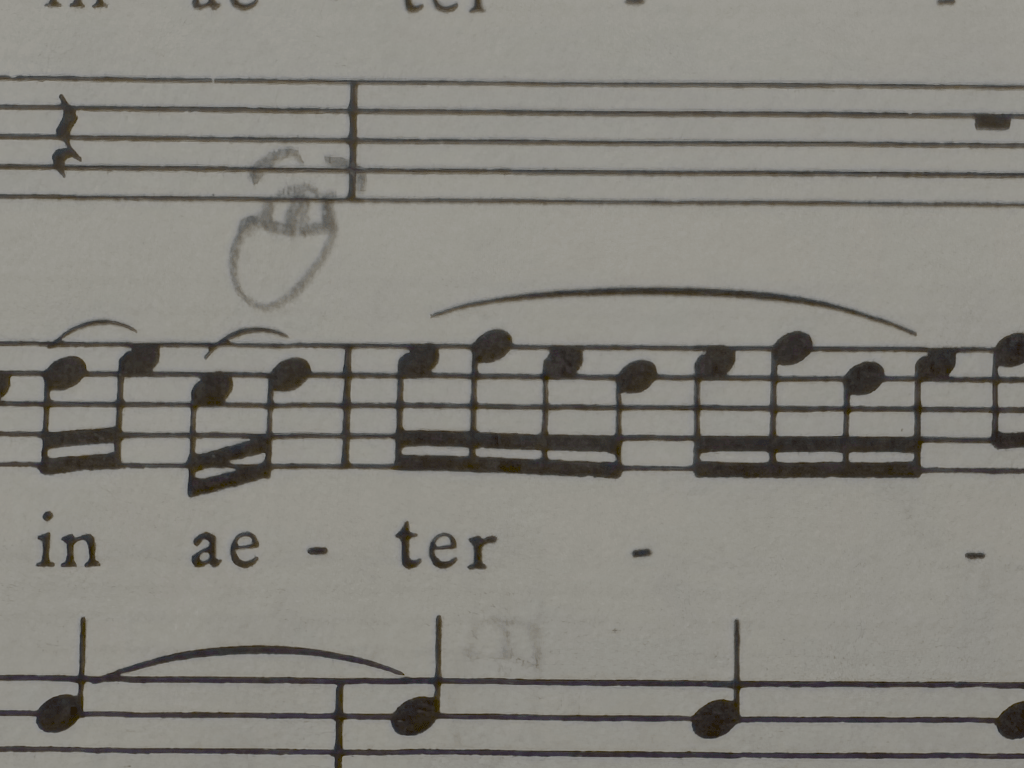

Following the storm of Destiny, we moved into Nänie. If Schicksalslied is about the struggle of living, Nänie is a meditation on the inevitability of the end.

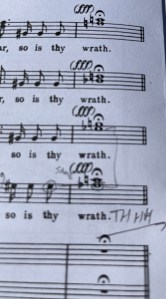

The opening line—Auch das Schöne muß sterben! (“Even the beautiful must die!”)—hits differently lately. In my own community, we’ve recently said goodbye to a friend’s brother and to a former member of our chorus. Singing these words is no longer just a rehearsal exercise; it’s a direct conversation with those losses. Brahms composed this choral work in memory of his deceased friend, with text from a Goethe-influenced playwright and poet, Friedrich Schiller, so his emotions and intent shine through.

Through the music, Brahms suggests that while death is an inescapable fate, the mourning process itself is holy. The text suggests that a Klaglied—a dirge or funeral song—on the lips of a loved one is a glorious thing. It’s a reminder that beauty, even fleeting, is worth the lament. Rather than trying to skip past grief, compartmentalize it, or optimize it away, sitting in the stillness of that lament is a necessary, almost joyous, spiritual recalibration.

Building the Chamber Sound

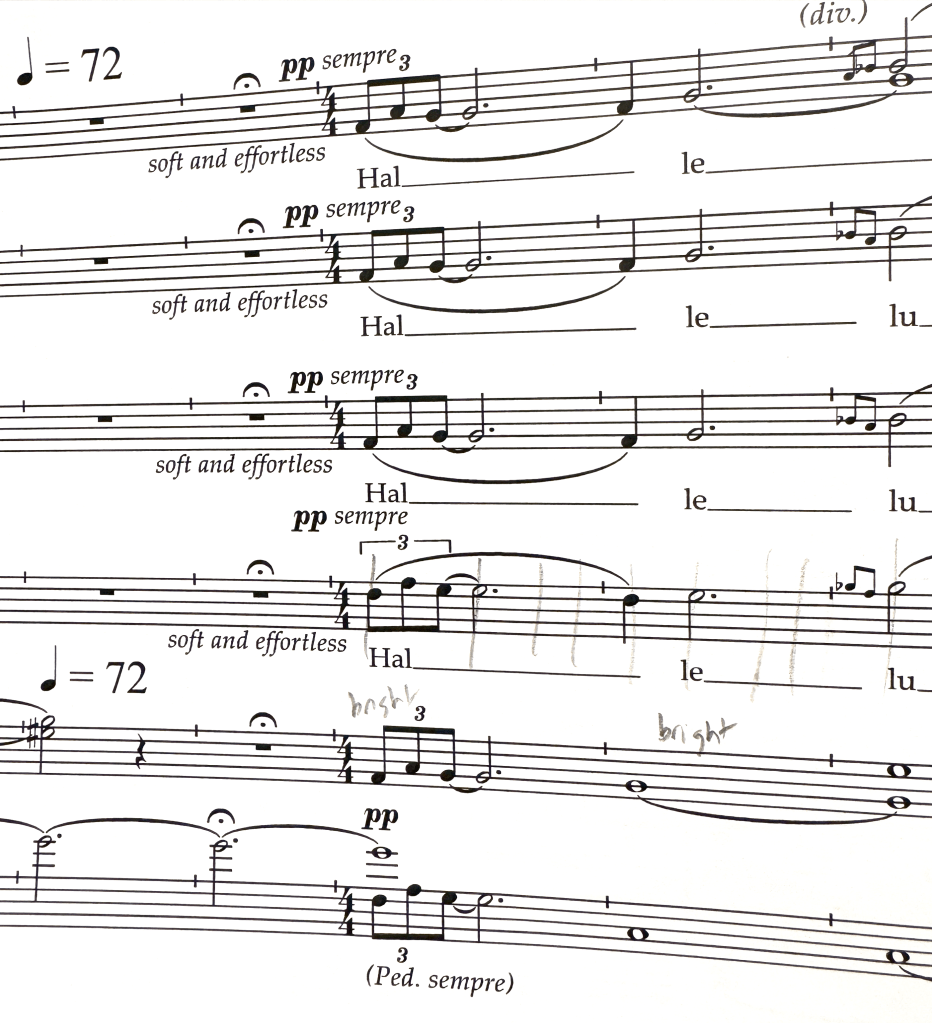

Before the orchestra arrived, we spent weeks under the direction of guest choral conductor Lisa Wong, who was tasked with refining our massive group into a nimble chamber ensemble. She focused heavily on a unified, zero-vibrato approach, a sound that our conductor Blomstedt also favored in our last sing with him. The thinking is that in Brahms’s dense harmonic structures, individual vibrato acts like static on a radio signal; by flattening the tone, the chords lock into place with ringing clarity, as well as better communicate the pianissimo moments of stillness in each piece.

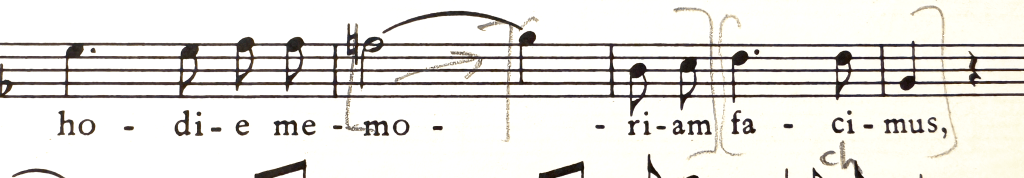

Wong had several rehearsal techniques geared towards achieving that uniformity of sound as if from a more intimate chamber chorus. We even spent time singing row-by-row, forcing us to listen as a small ensemble rather than relying on the safety in numbers of a large chorus. She paired this intimacy with her own relentless focus on German diction—not just for the sake of the language, but because uniformity of vowel sounds and the sharp, percussive snap of German consonants confer that uniformity of sound… not to mention they give the “Fate” sections more driving energy. Finally, she reminded us that the performance be reflected in our faces. It’s hard to believe in the unhurried movements of the gods or the desperation of humanity if you look like you’re reading a grocery list. I certainly relished channeling those previously mentioned frustrations as well as moments of quietude directly to my body, willing the audience to viscerally experience the transition from celestial peace to human struggle.

The Maestro Returns

Once groundwork was laid, we were ready for the now 98-year-old Herbert Blomstedt. Seeing him at that first piano rehearsal, with a walker and a two-person assist just to ascend to the podium, made me remember having similar doubts in 2018 when he led us in the Lord Nelson Mass at 91. With a mischievous glint in his eye as he settled on his stool, he dispelled those concerns by assuring us that everything still worked “from the waist up.”

Maestro Blomstedt’s essence is the same, though he’s traded some of his fieriness for conducting that is more distilled and conservative. No wasted motions, for sure! He doesn’t need to flail to get a fortissimo; he simply commands it through presence and a century’s worth of musical intent. The challenge for the singer is that those small gestures require more visual tethering. If you rely on your own internal clock, you’ll likely outrun him… as we unfortunately did a few times in rehearsal and once in the first performance. He takes these pieces at luxurious, expansive tempos that allow the music to breathe and shimmer. However, that means you have to really watch to catch his subtle pulling of the reins.

In rehearsals, he pre-shaped musical lines with suggestions for subtle dynamics, pushing us toward that ultimate goal of any conductor, distilling his interpretation of the composer’s intent into the performance. He spoke as well of the need to bring back hope as per the coda of the Schicksalslied, and to bring honor to the mourning of Nänie. As a spiritual man himself, it’s so clear he draws energy from leading these performances, and we’re all too happy to reflect it back to him.

Gathering and Scattering

The true test of all this preparation is the performances. When Maestro Blomstedt appeared, slowly making his way to the podium with his walker, the audience erupted. It wasn’t just a polite greeting; it was a massive, sustained ovation that felt like a collective “thank you” for a century of musical dedication. How often do you see a crowd so moved just by a conductor arriving? Then again, I’d applaud a 98-year-old man just for making it across the stage, let alone assuming command of an entire symphony and chorus.

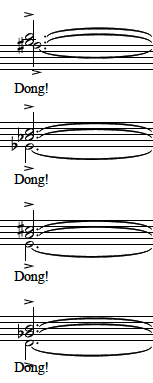

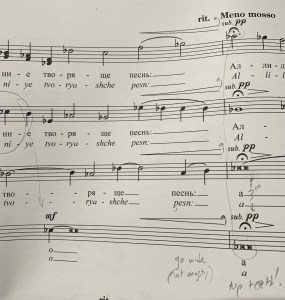

During the performance, a music teacher friend noted a specific phenomenon that really captures the Brahms experience: the “Gather and Scatter” effect. During pianissimo moments of stillness—the quiet “Klaglied” of Nänie or the ethereal opening of Schicksalslied—the audience leaned in. You could feel the room “gathering” together, hushed and focused, trying to catch every subtle vowel we had worked so hard to unify. Then, when the “Fate” sections arrived, that gathered energy was “scattered.” The sheer force of the brass and the percussive snap of our German consonants pushed the crowd back into their seats. It was a visceral, physical dialogue between the stage and the house. I’m looking forward to two more performances.

The Final Reset

As we reached the end of the program, I thought back to the Maestro’s rehearsal comments about hope. By returning to that heavenly theme at the end of Schicksalslied, Brahms points to a way out of the chaos, or at least suggests help is on the way. To me, this is what it means to “touch grass” musically. We spent a half hour contemplating the inevitability of death and the randomness of fate, yet we walked off the stage feeling lighter.

In a world that can sometimes feel like it’s spinning out of control, it’s incredibly grounding to be part of a ~120-person “chamber” chorus, guided by a 98-year-old legend, all dedicated to the simple act of mourning and hoping together. If the goal was spiritual recalibration, we hit the mark.

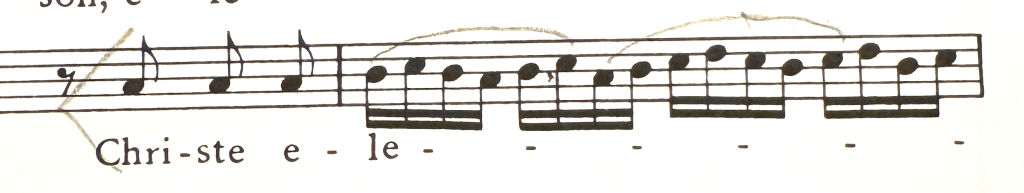

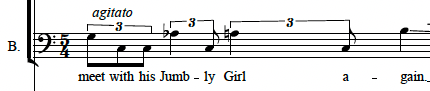

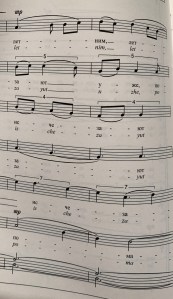

The second movement in particular is challenging (except for us basses, who have the luxury of holding pedal tones throughout). Parts overlap in rhythms of 4’s, 5’s, 6’s, and 7’s to create this many layered buildup of individual phrases stacked like warm covers on your bed in the winter. It reminds me very much of the second half of

The second movement in particular is challenging (except for us basses, who have the luxury of holding pedal tones throughout). Parts overlap in rhythms of 4’s, 5’s, 6’s, and 7’s to create this many layered buildup of individual phrases stacked like warm covers on your bed in the winter. It reminds me very much of the second half of