The Tanglewood Festival Chorus is once again taking on the Mozart Requiem—another in the pantheon of choral works that audiences adore and turn up on concert programs like clockwork.

I’ve written before about singing the Requiem under the baton of Michael Tilson Thomas in 2010, and again with Andris Nelsons in 2017 with James Bagwell doing the honors in chorus prep. (Even interviewed him for a podcast.) Somewhere along the way I swore I’d never turn down a chance to sing the Mozart Requiem.

And here we are again. But as with those last two performance cycles, there’s always something to discover. No matter how many times you sing a piece, a good conductor (or two) will reveal entirely new dimensions to put a new face on an old friend.

A New Layer from James Burton

The TFC”s choral conductor, James Burton, had a lot more to work with than given almost all choral members knew the notes from the very first rehearsal. That meant he could focus on technique and musicality instead of simply rhythm and dynamics. So it was up to him to take this well-worn repertoire and coax new life from it—not by reinventing the wheel, but by refining it. His emphasis on vowel production might sound like standard choral fare, but his approach quickly got granular in ways that matter. Sometimes that took the form of obvious reminders, such as his guidance on cleaner vowel transitions with no sudden “yuh” or “wuh” between vowels. But it was also about getting a better response back from Symphony Hall itself.

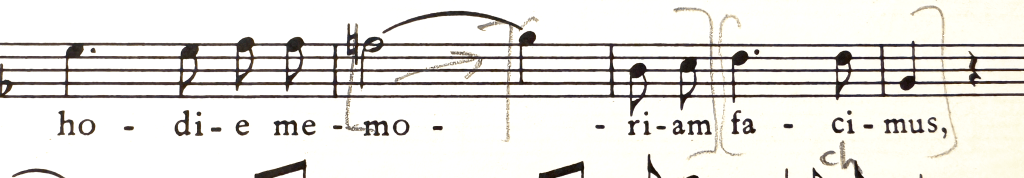

Really, most of his vowel coaching was about shaping our mouths to resonate in a way that keeps the sound spinning. I even developed a new marking in my score—two tiny squares in a circle—to remind me to “show my top teeth” for the ideal /e/ vowel. Want to sing /o/? Make it sound more like “ah” and bring it forward. Want an /u/ with presence? Start with the space of an “ah,” then curve your lips around it without losing that raised soft palette. You could really hear the difference in an empty Symphony Hall during rehearsals when we adopted these techniques. “The Hall likes that,” James pointed out as the resonance filled the space. It also gave us more control over dynamics and more efficient breath.

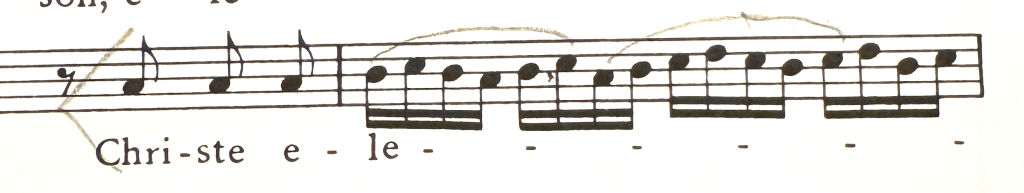

His other big focus was phrasing, in two ways–the first being shaping them. More than once he urged us not to wait to be musical. “You’ve got four of the same note,” he challenged us. “What are you going to do with that?” He also reminded us that the style of the time was to “drop the dot” by turning dotted quarter notes into quarter notes and using the extra space to rearticulate the following phrase.

The other coaching was in the relationships of phrases to measures and their downbeats. For instance, acknowledging hemiolas in the Hostias movement made a noticeable difference compared to charging through them as I had in the past.

Another example is in the opening and closing fugues. THey have a particular figure that basses normally thump through in rigid 4-note groupings, but James urged us to change it to larger phrases that made a lot more sense developmentally.

The end result was a well-prepared chorus armed with musicality and responsive enough to react to the adjustments that would come from our guest conductor, Dima Slobodeniouk.

Enter Dima: Refining the Shape

Once James handed us off to Maestro Dima, the details only deepened.

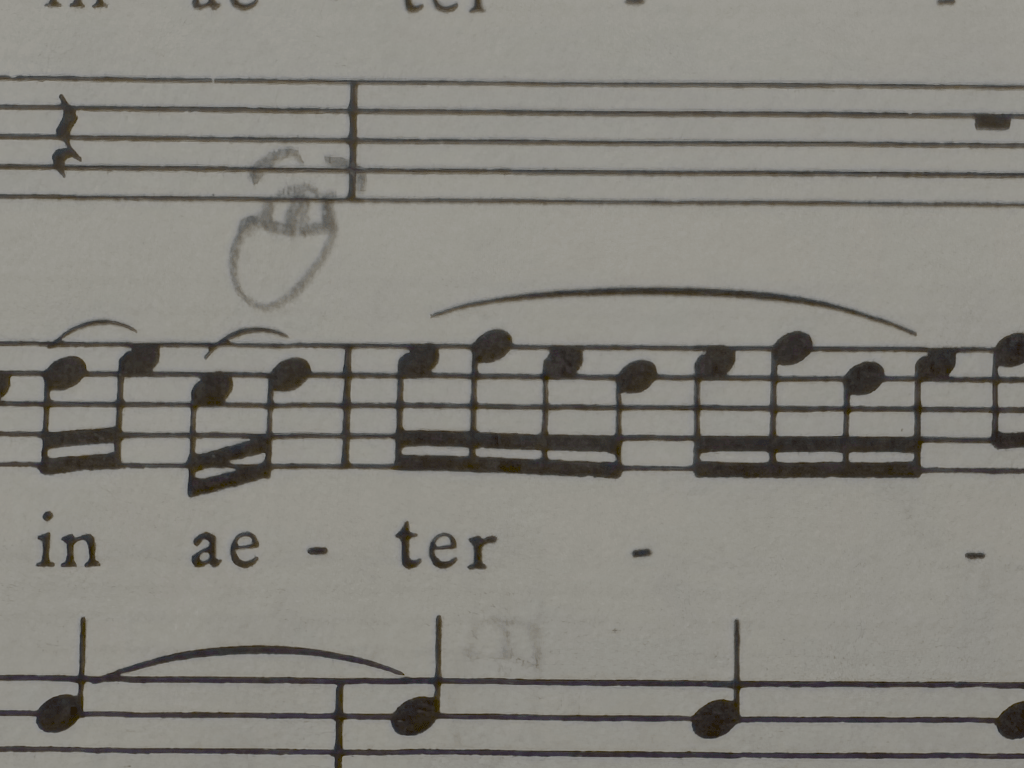

Dima’s approach brought a mix of precision and lightness, a chamber-music sensibility even within the scope of Mozart’s larger-than-life drama. (At times for us basses, it felt like he was trying to get elephants to do ballet. But let the record show, we tried.) Practically speaking, that often meant crisp articulation—like singing Rex shorter and sharper, letting the “ks” bounce through the hall. Or asking for more marcato when singing lux aeterna, so it cut cleanly through the orchestral texture. His favorite coaching words were “transparency” and “organically,” to give a more ethereal, more natural story-telling nature to the piece rather than the ponderous plodding you’d get from a pick-up choir at a summer sing.

Dima also took steps to treat Symphony Hall itself as an instrument. He’s adjusted dynamics and articulation not just for musical effect but to optimize how sound travels in that space. The Dies Irae, for example, isn’t always a full-on wall of fortissimo–the second time through we back off and leaned into a swell of phrasing. In one moment, we shaped quantus tremor as a gradual decrescendo—mf to mp to p—then hit a subito forte, the timpani sforzando removed to preserve the surprise.

In prep time, James pointed out to us that when we sing Pie Jesu midway through the piece, it’s the first time we say Jesus’s name. “Don’t you think that should be a special moment?” So we were already treating it differently before we made it to the piano and orchestra rehearsals. Well, Dima apparently agreed, because he exhorted us to make that first Jesu “impossibly gentle,” with a space after it akin to railroad tracks before finishing the thought.

Dima was also focused on bringing out the interplay between voices, asking us to bring out the bouncing back and forth of imitative stretto entrances across the voices. In many cases that included interplay with the orchestra, asking us to key off of their entrances or asking them to pull back and be supportive of ours.

Perhaps most impressively, when working with the Boston Symphony Orchestra… well, let’s just say Dima wasn’t shy asking to get exactly what he wanted. He worked explicitly with some sections to get the tempi, pulse, and intonation he wanted from them.

The Familiar, Made Fresh

So here we are: another go-round with Mozart’s (and Süssmayr’s) final masterpiece. And yet, thanks to James, Dima, and a roomful of singers who still care, it still feels compelling and rewarding to be a part of it.

Maybe that’s why I keep saying yes to this piece. Not because it’s easy. Not because it’s new. But because with the right polish, even a battle axe can gleam.

Pingback: Mozart Requiem, and the Promisistini – Jarrett House North