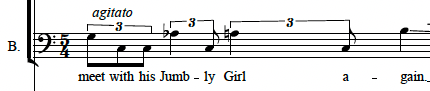

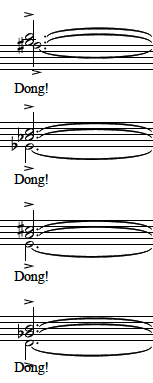

Every once in a while, I get to take part in a performance that adds something new to the world. Not just a new interpretation of a classic work, but an actual premiere—something no one’s heard before. Past highlights have included James MacMillan’s moving St. John Passion and Elena Langer’s delightfully strange The Dong With a Luminous Nose. This week, the Tanglewood Festival Chorus gets to introduce another such debut: the world premiere of Love Canticles, composed by Aleksandra Vrebalov and commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

For the composer’s biography, background, and official program notes, the BSO has done its homework right here. You’ll read about her Yugoslavian roots, her longstanding collaboration with the Kronos Quartet, and her deep ties to Tanglewood. Love Canticles draws inspiration from Psalms 103 and 104, hymns of praise that focus on divine mercy, human mortality, and the spirit of creation. Designed as a companion to Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms—which shares the orchestration and the Biblical inspiration—it’s a thoughtful pairing that gives the pre-intermission program a thematic arc.

But my blogs aren’t history or theory lectures. They’re about the experience itself, namely: what’s it like to learn and rehearse a world premiere like this?

Modern Composers and Their Toys

One thing I’ve learned from these modern premieres is that contemporary composers love their toys. Not just odd harmonies or quirky rhythms, but full-on “wait, what did I just hear?” moments.

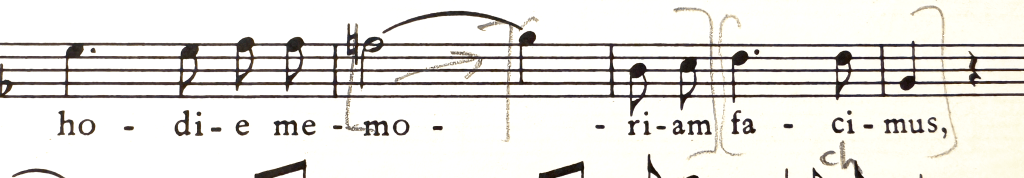

MacMillan’s piece gave us gimmicks like winding-down slides, haunting melismas, and murmured text. Langer leaned into tremolos, tone clusters, and cheeky motifs. Vrebalov, in turn, gives us three main tricks—each one adding a distinct texture without feeling too gimmicky or overindulgent.

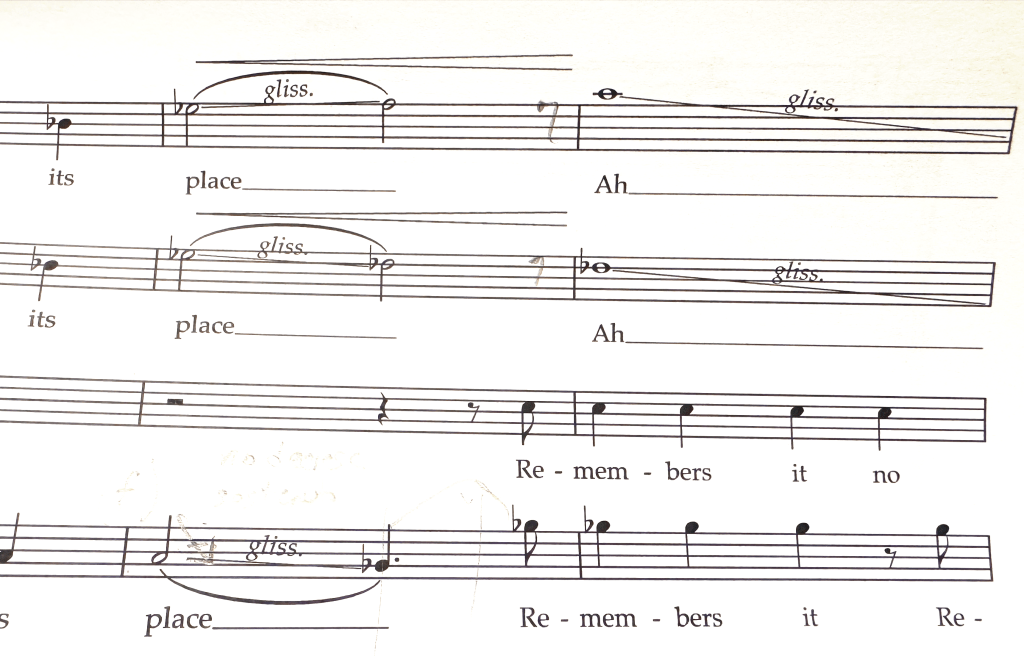

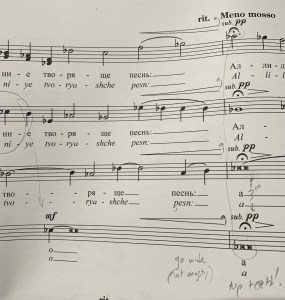

First, her use of the glissando. At several points, Vrebalov emphasizes an interval or transition by asking the chorus to glide between notes. Unlike a portamento (a more gradual, often expressive slide), these glissandi start immediately, even between two adjacent pitches. This controlled Doppler effect sends a subtle chill down the spine, especially when the resonance lines up just right.

Second, the choral soloist moments. It may be a single baritone or tenor that hangs onto a note “as long as comfortable” after everyone else cuts off. It may be a soprano floating an isolated note across bar lines. Twice Vrebalov calls for a “solo soprano invocation, sprechstimme.” For those unfamiliar: sprechstimme is the half-spoken, half-sung style popularized by early 20th century expressionist composers like Schoenberg. (Though maybe popularized is the wrong word — let’s just say if sprechstimme had a fan club, it’d probably meet in a very small practice room.)

Finally, the quirkiest delight: morse-code chattering. We’re instructed to sing two alternating notes “random, like morse code,” or later “random, not too fast, breathe ad lib, within the beat.” The result? A soft, percussive texture—part chittering insect, part tonal snowstorm—nestled beneath melodic lines and an ethereal orchestral shimmer. It shouldn’t work. And yet, it absolutely does.

Technical Challenges, Emotional Payoff

Despite the avant-garde gestures, the piece has been surprisingly accessible to learn. (Perhaps more so for us basses, who merely hum a low note for the first 30 bars. Sorry not sorry.) The rhythmic shifts and subtle tempo changes keep us alert, but the score is clean and communicative. Now if I could just figure out how to count some of these triplets…

Unlike re-learning the Mozart Requiem—where you can choose from hundreds of different recordings, all with idiosyncracies that don’t match your current conductor’s choices—Love Canticles has no recordings, having just been finished a few months ago. We’re the first voices to give shape to these markings, dynamics, and gestures. It’s up to us to breathe life into the dots on the page.

James Burton, our conductor, has been carving space to talk about the music’s character (when he’s not reminding us to please observe the clearly marked accents, dynamics, and rhythms). “You’re psalmists,” he said recently. “Find joy in this. Or else, why are you here?”

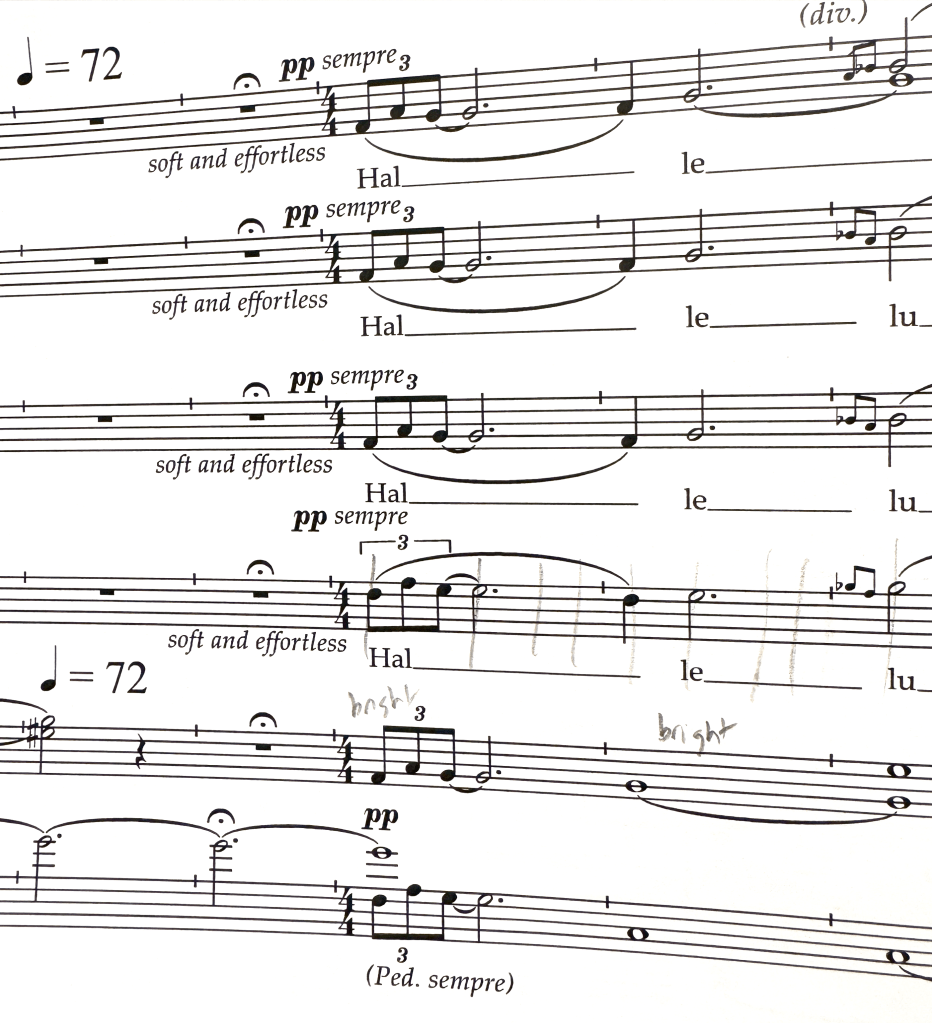

Not every passage is joyful, though. The text and the music wander through questions of impermanence, vulnerability, even anger and defiance. And then, emerging in the final measures, Vrebalov gives us an extended Hallelujah—optimistic, weightless, and glowing. It’s an unbarred cadenza of calm, an unadorned F-major from nowhere that provides a sempre pianissimo moment of grace after all the histrionics and questioning. It’s not an answer, but it is a release.

Dead Men Tell No Tales

One benefit of performing living composers? They can show up and tell you what they actually meant by what they wrote, say over lunch. Dead white European men can’t tell you what they want. But in our final rehearsals this week, we’re expecting notes from Aleksandra Vrebalov herself. It’s a rare gift to be able to ask, “Was this the sound you imagined?” and get an answer.

How exhilarating it must be for her to write for a chorus and orchestra she’s long admired, then to hear her own music rise up, live, for the very first time. And how lucky for us, to be the ones bringing it into the world. We’re looking forward to singing these psalms of praise for her and our audience this weekend.

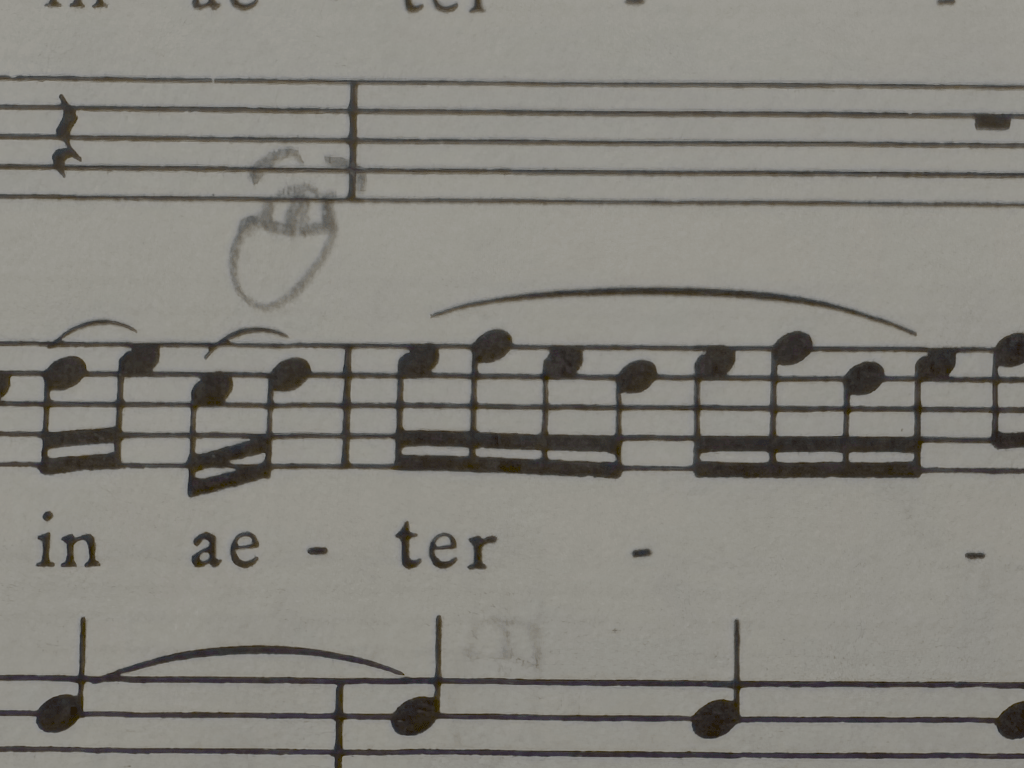

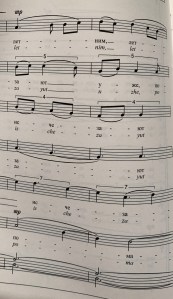

The second movement in particular is challenging (except for us basses, who have the luxury of holding pedal tones throughout). Parts overlap in rhythms of 4’s, 5’s, 6’s, and 7’s to create this many layered buildup of individual phrases stacked like warm covers on your bed in the winter. It reminds me very much of the second half of

The second movement in particular is challenging (except for us basses, who have the luxury of holding pedal tones throughout). Parts overlap in rhythms of 4’s, 5’s, 6’s, and 7’s to create this many layered buildup of individual phrases stacked like warm covers on your bed in the winter. It reminds me very much of the second half of