страданье, гнет, and борьба! The Russian words for “suffering, oppression, and struggle” sum up the Russian gestalt, as my good friend the Crazy Russian Dad confirmed. (He also suggested the chorus buy and wear these Ushanka hats, but alas, I don’t think they meet the summer dress code.) That is the world we’re entering as our chorus finalizes its preparation to sing Shostakovich’s 2nd Symphony on Friday evening at Tanglewood.

страданье, гнет, and борьба! The Russian words for “suffering, oppression, and struggle” sum up the Russian gestalt, as my good friend the Crazy Russian Dad confirmed. (He also suggested the chorus buy and wear these Ushanka hats, but alas, I don’t think they meet the summer dress code.) That is the world we’re entering as our chorus finalizes its preparation to sing Shostakovich’s 2nd Symphony on Friday evening at Tanglewood.

Both our Russian diction coach (Olga Lisovksaya) and BSO conductor Andris Nelsons spoke to us about the Soviet legacy, since both grew up under its shadow. They recounted the brainwashing in schools insisting that Lenin was the country’s god and savior. The two implored us to get past the distasteful propaganda-heavy text and sing the music for what it was. But honestly, I didn’t think that was too hard. Every time we sing a piece we are acting, whether we’re pleading to be spared God’s wrath, gluttonously worshipping false gods, or sadly bidding farewell to our maimed star-crossed king. Heck, for Holiday Pops, Christian chorus members sing joyful Hanukkah songs and Jewish chorus members sing reverently about the Nativity. Is this that different?

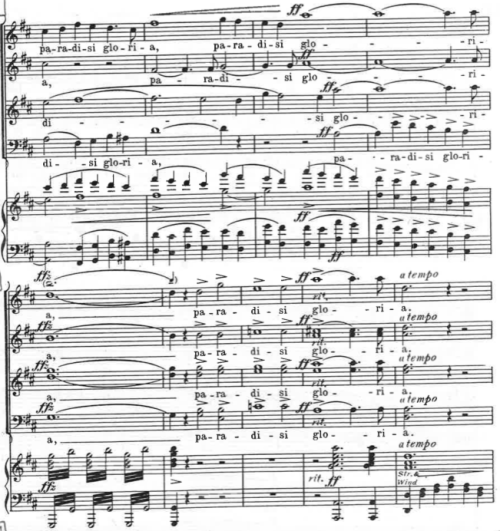

This symphony, however, is odd. The composition includes some “abstract music” with unusual layering effects. It was commissioned to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. Shostakovich himself didn’t like the results, calling his 2nd and 3rd symphonies “completely unsatisfactory,” as he struggled setting the words to music. The piece itself is rarely performed, unless a group (such as the BSO) decides to do a Shostakovich cycle. In fact, our choral scores were assembled just for us: the Cyrillic transliterated, the music photocopied, the pages spliced together from disparate parts.

Having somehow dodged performing Stravinsky’s Les Noces and Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky, I finally had to learn how to pronounce Russian consonants and vowels that don’t exist in the English language (hint: it’s all in how you palatalize your tongue). I learned to be a good little Soviet who can sing the praises of Ленин and his revolution.

If you’re listening this Friday night, here’s what to expect during these 20 minutes. The first section reportedly represents the chaos before order emerged, as clusters of instruments compete for attention. Then, there’s a meditative section described by Shostakovich as depicting a child killed on the streets. After that, more funky music including some beautiful solos. And then the triumphant propaganda of the Oktober Revolution by Lenin, jarringly introduced by (I kid you not) a factory siren. In fact, Andris and the orchestra are still debating whether the siren should go full blast or stop at an F# for us to tune to.

While it won’t go down as my favorite Tanglewood performance, it’s been fun to lean into the role of devoted proletarians. At one point, Andris told us he didn’t think we were capturing the fervent adoration of the cult of Lenin when we shout his slogans before the finale, so he gave us this direction in his halting English: “I haven’t partaken of this, but… you know that new cannabis store that opened by the highway, with lines of cars around the block? Act like you’ve been there.” That’s right, baby… we’re high on Lenin this Friday!